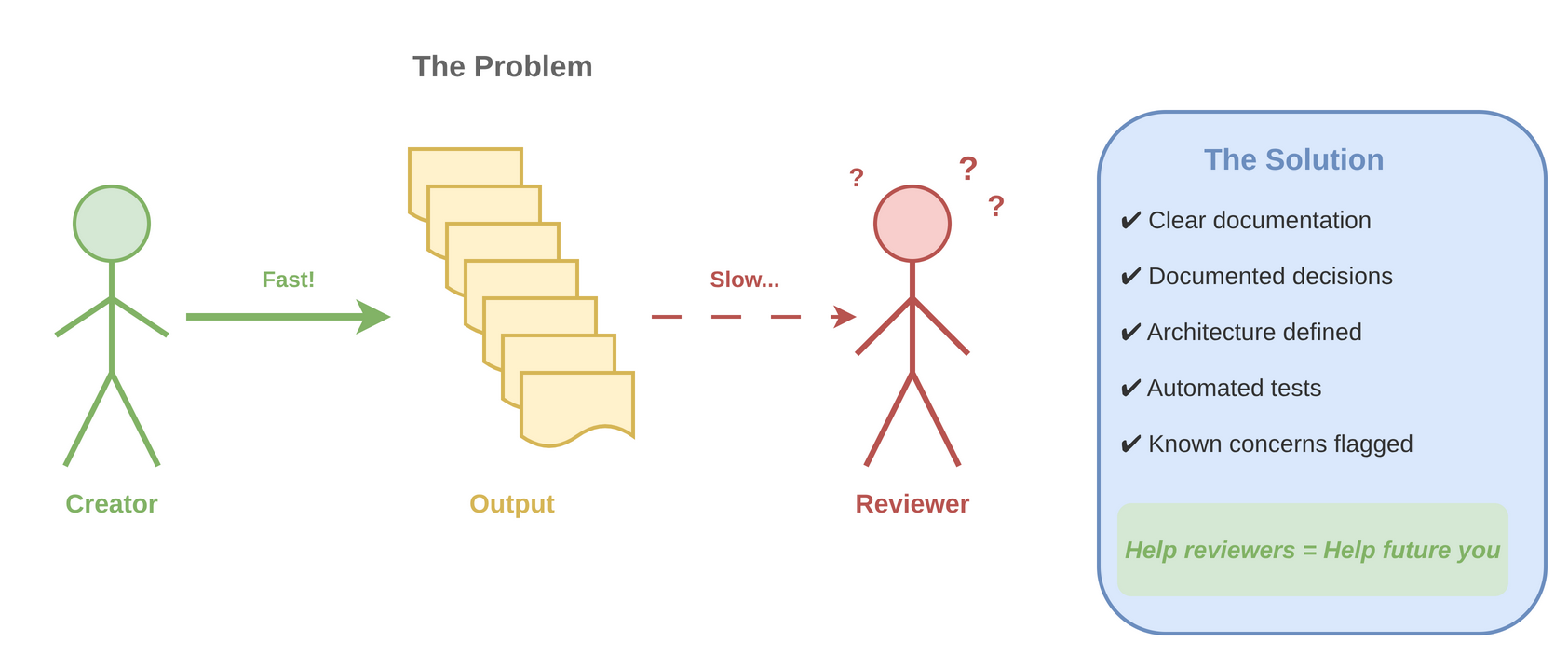

🔍 It is often more work to review something than to do it

As an experienced person, I am sometimes called on to review something. This can be a frustrating, seemingly hopeless task. With one developer, I commented that he could write code faster than I could review it. While there are some issues you can spot from a cursory look, most issues are subtle in nature—otherwise the original designer would have probably caught them. Therefore, you pretty much have to go through the entire design exercise again (especially with hardware) to find issues. In many cases, it would have been faster to simply do it yourself. This is the quandary many experienced developers find themselves in when working with junior people. They are responsible (because they are the reviewer), but feel helpless to ensure quality.

This is also the quandary we find ourselves in with AI. AI agents can write code much faster than any human can practically review. Therefore, the thought that "with AI code, as long as we review it, we're good" is delusional. We might pretend we are doing it, but deep inside we know we are not. AI coding has brought this into stark reality.

Too often, reviewers receive schematics or source code with little context. What are the goals? What is the spec? What trade-offs were considered? What calculations were done? What edge conditions were considered? What is the architecture? Details without the big-picture context are very difficult to work with. While I've not often been party to formal code reviews in a meeting context, I suspect these could work better than offline asynchronous reviews because you can ask the designer questions and perhaps get some insight into the potentially weak areas of the system.

There are ways we can help reviewers:

- Clear documentation about the requirements located in the same repository as the design/code.

- All assumptions, decisions, calculations, etc. are documented. With schematics, as much of this as possible should be included directly in the schematic. Use more pages if needed.

- Architecture is clearly defined and documented.

- All testing is documented.

- All assumptions are documented.

- Automated tests are created where possible.

- Performance metrics and resource usage are documented and automatically tested if possible.

- Any concerns, potential weak spots, or things we're not sure of are clearly documented. Often the designer is the only one who has insight into this.

The point many miss here is that if we do the above, we're mostly helping ourselves 6 months from now.

As systems become more complex, it seems the only practical path forward is automated testing. Chip designers figured this out a long time ago as the cost of errors is high with full-custom silicon. Software developers are pretty good at this with TDD (test-driven development). But, the industry needs to go one step further and embrace end-to-end testing (which includes both hardware and software). Perhaps the most important role of a reviewer going forward is to ensure adequate documentation exists and tests are in place. Anything else is futile and we're just pretending.